Let me say first that it’s an extremely important day for this blog, as I put the proverbial pen to paper to wax poetic about one of my favorite movies ever: The Mummy. The 1999 Stephen Sommers action-reinvention of the classic Boris Karloff film of 1932 found the ineffable Brendan Fraser nearing the height of his admittedly short stretch of box-office power, and scratched all of the right itches in terms of what 7-10 year old Cory was looking for in a movie, filled to the brim with corny romance, adventure flick setpieces featuring swordfights and gunfights, and a dash of humor. It was a giant in terms of sleepover DVDs, rivaled only by Rush Hour in the family movie collection, and yet in spite of that fact – and a pretty phenomenal box office run that resulted in two sequels, one amazing (The Mummy Returns) and one not-so-amazing (The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor) – its critical returns were minimal at best. Bearing that in mind, and also bearing in mind the fact that superstar Tom Cruise semi-recently proved that mummy movies don’t always work out, I can’t resist trying to identify just one of the many ways in which The Mummy is ultimately a success, and to do so, I’m going to get slightly esoteric a la my recent post on The Shawshank Redemption.

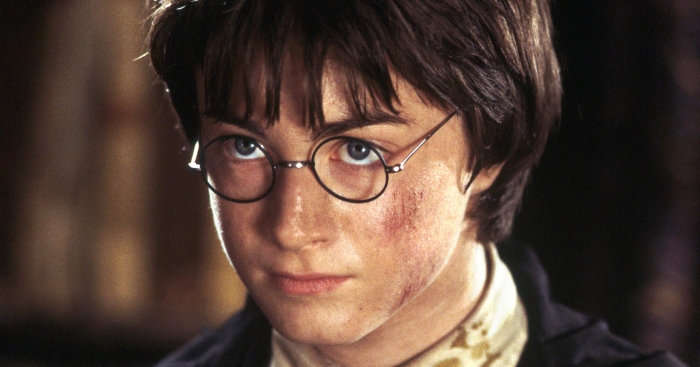

Brendan Fraser: not as good of a runner as Tom Cruise, but definitely the better frontman for a mummy movie.

In my continued quest to better understand what makes movies, or specifically movie scripts, bad or good, I’ve been periodically engaging in some light quarantine nonfiction reading in the form of The Anatomy of Story, by John Truby. It’s a book that one of my favorite screenwriting YouTube channels cites frequently in its video essays, and it’s one that I would (thus far, I’m only about halfway through) recommend to anyone who has a passing interest in this sort of thing. Recently, in his chapter on character, and specifically in the context of building conflict between characters, Truby talked about the concept of four-corner opposition, in which rather than simply pitting a hero against one opponent, he or she is also pitted against two secondary opponents. There’s a great video about the method here, presenting Batman Begins as an example, that probably explains it better than I ever could, but immediately after reading about it I thought about how the technique – which involves the multiple opponents attacking each other in addition to the hero – could be applied to some of my favorite movies. While I’m not here to claim that The Mummy is a stroke of screenwriting masterpiece (it is, but whatever), I think the four-corner opposition model has been reasonably applied within its structure, deepening a central conflict that at face value seems very pedestrian and further fleshing out the primary weakness, and weakness in values, of our hero.

This dynamite has the longest fuse of all time.

It’s not hard to establish two of the four corners in our box when we think about The Mummy. The hero is of course Brendan Fraser’s Rick O’Connell, and his primary villain is Arnold Vosloo‘s Imhotep, the titular mummy. Establishing the other two corners is slightly less clear, but for one of them I’ll select Oded Fehr‘s Medjai Ardeth Bay (largely due to the strength of his conflict with both Rick and Imhotep) and for the other, Rachel Weisz‘ Evie. Mummy viewers reading this are probably at this point scratching their heads wondering why/how Beni and the Americans (who are the constant subject of derision by the hero and his friends, specifically Jonathan) fail to fit into this structure, but the conflict between those characters and Rick is too surface-level, and by the end of the movie they more or less serve as cannon fodder. Evie may seem like a comparatively counterintuitive choice in that she’s on Rick’s side for pretty much the whole movie, but it’s important to note both the fact that she’s Rick’s love interest (Truby mentions in this chapter that in romances or romantic comedies, the hero-opponent structure of a typical screenplay is actually relatively unchanged, with the love interests serving as hero and opponent) and that her values as a character directly come into conflict with Rick’s more rugged sensibilities pretty much constantly.

Rick O’Connell’s approach to every problem: shooting it.

Because in terms of drama, the main job of these opponents is not to take over the world, or stop someone from taking over the world, or even simply survive. Their job – at least according to Truby and many dramatic experts – is to attack the weakness of the hero, and in our case, Rick’s weakness is that he refuses to believe in mummies, or curses, or reanimation, or basically in a lot of what happens in The Mummy. It’s only a whole movie later, in The Mummy Returns, where he quite literally claims to be a believer in a spoken line, and so a lot of the work of the surrounding characters in The Mummy involves getting him to stop being the Han Solo of ancient Egypt, either via a profound knowledge of Egyptian history (in the case of Evie) or via a lifelong vow to keep Imhotep from being awakened (in the case of Ardeth Bay) or via opening your mouth four feet wide and shooting a swarm of flies out of it (OK, you probably know who I’m referring to there). As someone who has occasionally tried to write things, one massive problem that makes it hard to even get through a scene is realizing that your characters have nothing to do, and four-corner opposition is the antidote for that poison, giving all of your important characters numerous fronts on which to fight. Another way to put it: if Rick, Evie, and Ardeth Bay simply banded together to fight Imhotep without getting into any scuffles of their own, The Mummy would probably be a lot more boring to watch.

This is all making no mention whatsoever of Jonathan, whose primary purpose at times seems to be to slow the entire plot down.

I’m probably – almost definitely – overstating the brilliance of The Mummy from a dramatic theory perspective here. It’s extremely unlikely that Stephen Sommers was thinking about anything even close to four-corner opposition when writing the movie – it’s far more likely that he was just thinking about having a good time, and he succeeded there too – but I also think that most movies to which the model can be applied fit in that same category. It’s unlikely that Christopher Nolan flipped open Truby’s book when he went to write Batman Begins, which is arguably a better example of this theory, and unarguably a more acclaimed movie, but the point is that while things like four-corner opposition aren’t necessarily rules to be followed, they’re the things that can often be identified in movies that are good after the fact. Dramatic theorists from Truby to Aaron Sorkin will waste no time recommending reading Aristotle’s Poetics to any aspiring writer, essentially claiming that it forms a set of rules that all competent drama on stage or screen must follow, and while I’m certainly not that dogmatic about it (and while I’m certainly nothing of a dramatic theorist) there are plenty of great movies that do follow those rules, and do have something at least somewhat resembling four-corner opposition.

Tune in next week for my discussion of The Mummy Returns, which will somehow be even longer.

But look – it’s far more likely that I still enjoy The Mummy for reasons having nothing to do with anything of this sort, especially considering the fact that my age wasn’t in double digits the first time I watched it. There’s a nostalgia factor for sure, and the immeasurable and often inexplicable charm of late-nineties Brendan Fraser, and there’s also the special effects, which for the time were at least moderately impressive, and above all there’s a carefree sense of adventure that I think a lot of adventure movies don’t have. At the end of the day, it might also be more intangible – the way Roger Ebert put it in his initial review sounds about right (“There is hardly a thing I can say in its favor, except that I was cheered by nearly every minute of it. I cannot argue for the script, the direction, the acting or even the mummy, but I can say that I was not bored and sometimes I was unreasonably pleased.”). The Rotten Tomatoes consensus (60%) is somewhat harsher, claiming that it’s difficult to make any argument for The Mummy being a cinematic achievement, and while I’m not sure that that’s true, I do think it’s true that not every movie needs to be a “cinematic achievement” to be good, or to be enjoyed. There’s a term for that (popcorn movie) that’s not nearly as pejorative.

The effects folks might have overdone it a little bit with the blue tint on Rick’s face here.

If you’ve read this far, good for you. You either have a lot of free time on your hands, or you love The Mummy (which based on conversations with people around my age might be a generational staple) as much as I do. It’s fitting to me, as I reflect in this last paragraph, that this is the longest post I’ve ever written for this silly blog, as The Mummy may well serve as the partner to one of my longest-running love affairs with a movie, and I’ve found it to be both a pleasure and a challenge to write about it in a way that involves some critical thinking rather than just heaping the praise it so abundantly deserves upon it. While this post is unlikely to generate remotely as much buzz as last week’s clickbait-y one did, I appreciate your showing up for it.